The Polynesian Wayfinders

Polynesian and Micronesian navigators traversed vast Pacific distances in small canoes without any modern instruments, relying instead on a system of environmental observation. This article is about wayfinding techniques centered on navigation on clues from the environment and star paths to set course.

Written by Team on .

Introduction

Across the immense Pacific Ocean, Polynesian and Micronesian navigators did ocean voyages that remain among the greatest feats of human exploration. Without any form of navigation tools such as compasses, sextants, they crossed thousands of miles of open water, finding some of the most remote islands on Earth.

Their navigation was a science without instruments, a living system of observation, memory, and environmental attunement. This article explores their origins, methods, and enduring legacy, and reflects on what modern wayfinding practice can learn from them.

-

Smart Summary

Deliberate Expansion: Settlement of the Polynesian Triangle (Hawaiʻi, Aotearoa, Rapa Nui) was intentional, proven by archaeology, linguistics, and experimental voyages.

Multi-Cue Navigation: Stars, swells, winds, clouds, birds, and phosphorescence combined into a dynamic mental map.

Oral Cognitive Systems: Navigation knowledge was preserved through chants, star compasses, and strict apprenticeships.

Historic Proof: Voyages such as Hōkūleʻa’s 1976 Hawaiʻi–Tahiti journey validated oral traditions.

Modern Revival: Wayfinding today supports cultural pride, sustainability, and alternative navigation epistemologies.

A Story on the Open Sea

"The Star of Home"

The canoe Te Moana Roa rose and fell with the slow, steady breath of the ocean.

At the bow, young Kainoa crouched, scanning the eastern horizon. Behind him, his grandfather — the pwo navigator — sat cross-legged, his eyes half-closed, lips murmuring a chant older than memory.

They had been at sea for twenty-six nights, sailing from Rarotonga toward the distant Tuamotus. There was no land in sight. The crew’s hands were raw from hauling lines, their minds heavy with fatigue. Even Kainoa, raised on the salt smell of the reef, felt the creeping edge of doubt.

That night, the sky was a vault of diamond points. The old man spoke without opening his eyes.

Hold to Hānaiakamalama until she climbs too high. Then steer for Ke Kā o Makali‘i. The swells will tell you if you wander.

Kainoa nodded, repeating the chant in his mind — a sequence of stars rising and setting, a map without ink. As the night wore on, the cold bit at his skin, but he kept the bow fixed on the horizon star, trusting the feel of the swells against the hull.

At dawn, the old man stood and pointed to a faint green blush under a lone cloud.

There. The lagoon speaks.

It was the first glimpse of their destination. The crew erupted into shouts and laughter, paddles dipping in rhythm, every man and woman suddenly stronger.

That night, safe in the shelter of the atoll, Kainoa understood the truth his grandfather had carried across decades of voyages: the ocean was not empty, it was a book, and every swell, star, and bird was a word in its pages.

1. The Great Expansion

Origins and Purpose

The deep understanding of their environment allowed the Polynesian wayfinders to perceive the ocean as "full of signs to steer by", leading to the development of highly sophisticated navigational practices. Their remarkable maritime exploits were made possible through a combination of intensive study, cumulative knowledge of natural signs, superb seamanship, and unwavering faith.

Current archaeological and linguistic evidence converges on a shared origin: the Lapita peoples, Austronesian-speaking mariners from island Southeast Asia. Around 3,000 years ago, they began a sequence of voyages that moved steadily eastward, first into the Bismarck Archipelago, then into the uninhabited islands of the central Pacific.

It is tempting to think of a “canoe” as a hollowed log. In reality, the Polynesian voyaging canoe (vaka moana, waʻa kaulua) was closer to a ship — double-hulled, with large triangular sails, and deck platforms capable of carrying dozens of crew, food plants like taro and breadfruit, and animals such as pigs and chickens.

Design Features:

Stability: Twin hulls for ocean swells.

Speed: Capable of sustained daily runs exceeding 150 km.

Repairable: Built in sections for easier replacement of damaged parts.

These were floating ecosystems, microcosms of island life, designed to arrive not merely with people but with the seeds of a functioning society.

Two-Way Voyages — Proof of Mastery

Evidence of return journeys is crucial. Hawaiian oral traditions, for example, describe voyages to and from Tahiti via the Tuamotus — round trips of several thousand kilometers. The transport of non-native crops, such as the sweet potato from South America, confirms extensive and sustained exchange networks.

This bi-directional travel required more than favorable winds; it demanded a deep, practical knowledge of seasonal weather patterns, current systems, and navigational cues.

2. The Wayfinder’s Toolkit

From Great Journeys to Great Skills: Key Navigational Cues

The double-hulled canoes of the Great Expansion were only as effective as the minds that guided them.

To steer thousands of kilometers across open ocean without instruments demanded more than bravery; it required a layered navigational system, built on acute observation, meticulous memory, and constant recalibration.

Where modern mariners might glance at a GPS screen, a Polynesian navigator carried an entire atlas in their head — an atlas written in stars, swells, winds, clouds, and the behaviors of living creatures.

The Star Compass

Celestial Bearings in a Moving World

The night sky was the primary anchor of direction. Navigators divided the horizon into a series of “houses” or points, each marked by the rising and setting of specific stars. These points, learned through years of observation and chant, acted as reference markers for steering.

Horizon Stars: Low on the horizon, just rising or setting — the most accurate for holding course.

Star Paths: Sequences of stars rising in succession along a desired bearing, allowing navigators to maintain direction through the night.

Zenith Stars: Passing directly overhead, these marked specific latitudes, acting as a kind of celestial “address.”

Ocean Swells

Feeling the Invisible Roads

To the untrained eye, the ocean’s surface is chaos. To a navigator, it is a structured grid of energy.

Long-period swells, born of distant storms, hold their direction for days. Navigators learned to feel the angle of the swell against the hull and maintain their course even without visible stars.

Special patterns, like the Marshallese dilep, could be detected as subtle shifts in pitch and roll — signs that the canoe was riding a “backbone” of waves between islands more than 100 km apart.

Wind and Weather

The Breath of the Pacific

Wind was both propulsion and compass. Navigators identified prevailing trade winds by their moisture, temperature, and accompanying clouds.

Some traditions mapped as many as 16 to 23 named wind points, each tied to seasonal changes.

Clouds were equally telling: “land clouds” form in predictable shapes above islands, and the green reflection of a lagoon can sometimes be seen on their undersides.

Birds, Fish, and Te Lapa

Living and Luminous Guides

Birds: Terns and noddies have fixed daily ranges from shore; their morning outbound and evening return flights could point to unseen land up to 75 miles away.

Fish: The presence of certain species hinted at reef proximity.

Te Lapa: A mysterious underwater light phenomenon, often seen before landfall at night, thought to be caused by reef-generated bioluminescence.

The Mental Chart

Dynamic and Relational

Rather than a fixed map, Polynesian navigators held a relational chart: the canoe was considered the still center, and the islands, stars, and swells moved around it. This constant mental updating allowed them to integrate dozens of environmental cues in real time.

From Ancient Horizons to Modern Insights

The navigational methods of Polynesian wayfinders were more than survival skills — they were a living science, blending observation, memory, and adaptation.

The table below distills these techniques, showing how each worked in its traditional context and how its underlying principles can still inspire solutions in today’s world.

| Method | Description | Application | Modern-Day Lesson |

|---|---|---|---|

| Star Compass | Dividing horizon into points marked by star rise/set | Steering direction at night, seasonal route planning | Using celestial navigation as backup when GPS fails; training pilots/astronauts in sky orientation |

| Star Paths | Successive rising stars along a bearing | Maintain course all night without compass | Project management “handoffs” — sequential milestones maintaining direction over time |

| Zenith Stars | Stars overhead at specific latitudes | Latitude estimation on N–S voyages | Satellite calibration using fixed astronomical references |

| Ocean Swells | Long-period waves with consistent direction | Maintain heading in poor visibility | Reading environmental “patterns” in data flow or market trends |

| Dilep | Wave “backbone” between islands | Detect land direction beyond sight | Using subtle data correlations to reveal hidden connections |

| Wind Compass | Horizon points named for wind types | Seasonal route selection, emergency reorientation | Renewable energy siting based on prevailing wind analysis |

| Land Clouds | Predictable cloud formation over islands | Land detection beyond horizon | Meteorology for disaster prediction in remote areas |

| Bird Flight | Fixed foraging ranges from land | Identify unseen islands | Wildlife tracking for environmental monitoring |

| Te Lapa | Subsurface light phenomenon near reefs | Nighttime landfall cue | Advanced sensor development for underwater mapping |

| Mental Map / Etak | Moving reference island concept | Progress tracking without fixed coordinates | Agile navigation in autonomous vehicles without GPS |

These techniques were not learned casually. Each was part of a larger body of sacred, guarded knowledge, passed through long apprenticeships and encoded in chants and stories. In the next chapter, we step into the school of the wayfinder — where navigation was taught not with charts, but with narrative, memory, and embodied practice.

3. The Art of Knowing — Transmission and Cognitive Mastery

Beyond Skill: A Sacred Science

Polynesian wayfinding was never just a practical craft. It was a tapu knowledge system — sacred, guarded, and deeply bound to identity and responsibility.

To become a navigator was to enter an elite lineage, a living chain of minds that carried the ocean’s memory from one generation to the next. This inheritance was not passed through books or charts but through years of embodied learning — on the sea, under the stars, and in the company of those who already held the knowledge.

The Apprenticeship of a Wayfinder

Training to become a navigator could take a decade or more. A pupil, often chosen in childhood for quick memory and keen observation, began with oral instruction ashore before venturing on short sea journeys.

Stages of Learning:

Observation: Sitting beside the master, listening to chants that described star positions, swell patterns, and seasonal routes.

Chant Repetition: Reciting sequences until they could be spoken in rhythm, without hesitation, even under physical fatigue.

Mental Mapping: Visualizing the canoe as the fixed center while “moving” islands, stars, and swells around it.

Practical Voyaging: Steering under supervision on progressively longer routes, starting with inter-island trips before open-ocean crossings.

Mastery Trials: Being entrusted to find a destination entirely on their own, under the watch of the master.

The process emphasized what researchers like David Lewis have called “over-learning” — drilling knowledge far beyond initial mastery to ensure it could be recalled under extreme stress, darkness, or bad weather.

Guardians of Knowledge

Because navigation meant survival, the knowledge was often restricted to a chosen few within a community. In some traditions, passing on this knowledge required ritual preparation and the blessing of the gods.

The pwo initiation in Micronesia, for example, marked the formal recognition of a navigator as a master — a responsibility as much as a privilege.

Cognitive Brilliance in Practice

From a cognitive science perspective, Polynesian wayfinders demonstrate extraordinary capacities:

Spatial Memory: Retaining multi-layered information about directions, distances, and environmental changes over days or weeks.

Sensory Integration: Simultaneously reading cues from the sky, sea, and wildlife.

Dynamic Updating: Adjusting mental charts in real time to account for drift, wind shifts, or cloud cover.

This mental adaptability was essential. A fixed map might become useless when a storm pushed the canoe hundreds of kilometers off course; a mental map could be recalibrated instantly.

The very idea that people without instruments, charts, or writing could have developed an elaborate and effective art was so foreign as not even to enter the minds of most Europeans.

4. Tupaia’s Map — Cross-Cultural Cartography

The Navigator Who Drew the Ocean

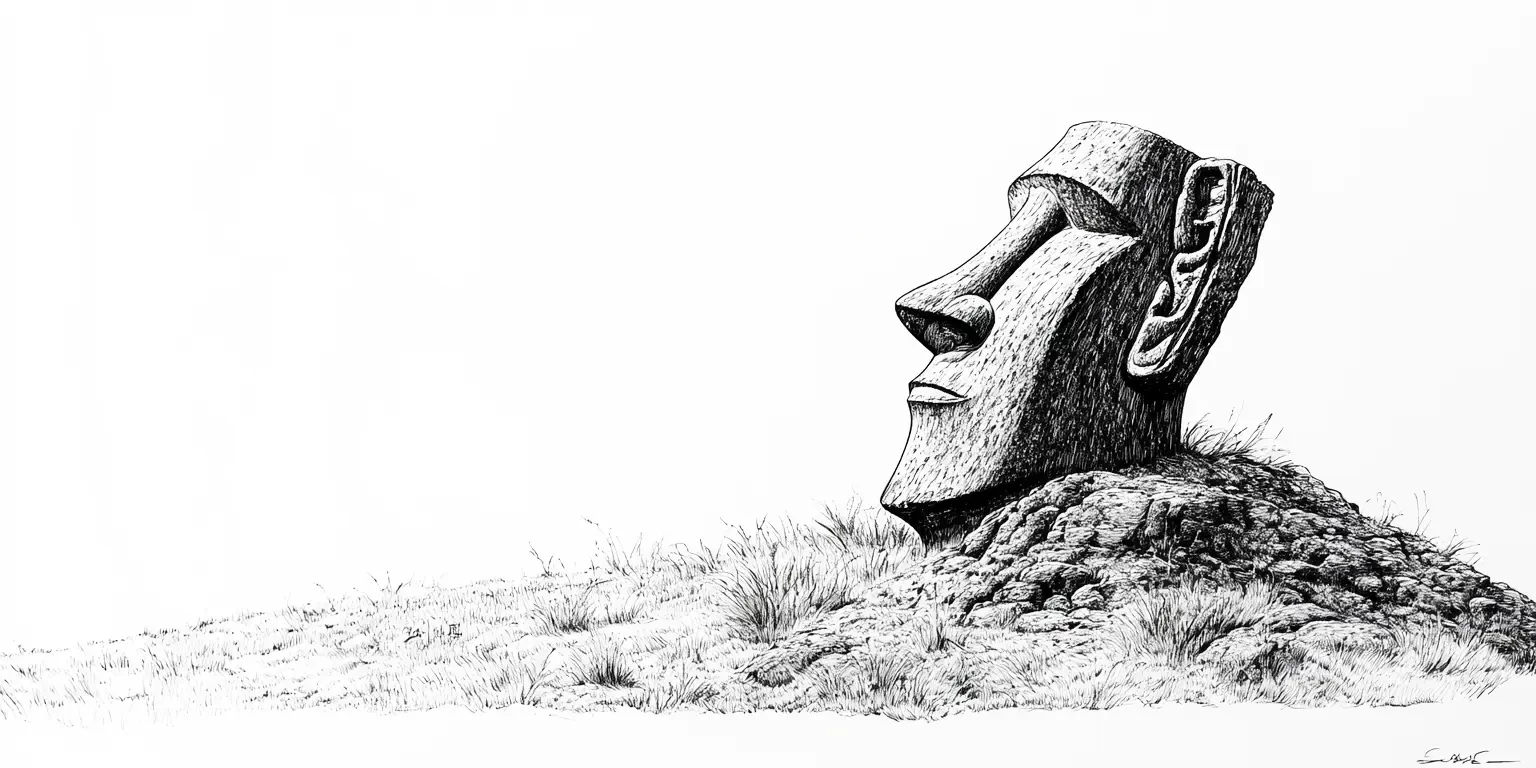

In 1769, the Polynesian master navigator Tupaia of Ra‘iātea stepped aboard Captain James Cook’s Endeavour.

A priest of the sacred marae of Taputapuātea and a man of immense voyaging experience, Tupaia carried in his mind a mental chart of the Pacific stretching from Rapa Nui in the east to Rotuma in the west, and from Aotearoa in the south to Hawai‘i in the north.

This knowledge was the inheritance of generations of navigators — but in the months that followed, Tupaia did something extraordinary: he translated his mental ocean into a physical drawing that European eyes could understand.

A Sea of Islands, Seen Through Polynesian Eyes

Tupaia’s map was not a conventional European chart. It was a knowledge assemblage, a fusion of two fundamentally different navigation systems:

Polynesian System: Relational, dynamic, based on bearings between islands as experienced by a voyager at sea.

European System: Fixed, abstract, using latitude and longitude anchored to a geographic grid.

At the map’s conceptual center was avatea — “the sun at noon” — which Tupaia used as a symbolic north. From this central point, he drew lines radiating to islands and archipelagos, each line encoding the direction and often the estimated travel time in days or nights.

Misinterpretations and Rediscovery

For decades after its creation, Tupaia’s map puzzled scholars. Lacking the cultural framework to interpret it, early European analysts dismissed it as imprecise or symbolic. Andrew Sharp even cited it as “proof” that Polynesians lacked the skill for purposeful long-distance navigation.

Modern scholarship, particularly the detailed work by Eckstein & Schwarz (2019), has overturned these views. By reconstructing the avatea-based bearings and comparing them to actual voyaging routes, researchers have shown the map’s remarkable positional accuracy — even across thousands of kilometers.

5. The Modern Renaissance

Reclaiming the Compass

In 1973, the Polynesian Voyaging Society (PVS) was founded in Hawai‘i with a bold mission: to build a double-hulled voyaging canoe and sail it from Hawai‘i to Tahiti without modern instruments.

The vessel was named Hōkūleʻa — “Star of Gladness,” a reference to the star Arcturus, an important guiding light in Hawaiian navigation.

In 1976, under the guidance of Micronesian master navigator Mau Piailug from Satawal, Hōkūleʻa completed the 2,500-mile voyage to Tahiti in 34 days, navigating solely by stars, swells, and environmental cues. This journey:

Silenced decades of academic skepticism about Polynesian navigational capability.

Inspired a cultural awakening across the Pacific.

Proved that ancestral knowledge, once thought lost, could still live.

From Ocean to Classroom

Wayfinding has found its way into modern education across the Pacific:

STEM Integration: Schools in Hawai‘i use the star compass to teach geometry, astronomy, and environmental science.

Cultural Education: Language, history, and environmental ethics are embedded in navigation training.

Youth Engagement: Programs bring young people aboard voyages to learn leadership and resilience alongside technical skills.

Relevance in the Modern World

Polynesian wayfinding’s revival offers lessons that extend beyond navigation:

Resilience without Technology: In a GPS-dependent era, these skills offer redundancy and independence.

Environmental Attunement: Wayfinding fosters an intimate, lived relationship with the natural world — essential for sustainable decision-making.

Cultural Continuity: The voyages restore pride, heal historical wounds, and connect diaspora communities back to ancestral homelands.

Cross-Disciplinary Insight: From neuroscience (studying spatial memory) to climate science (using voyaging to raise awareness), wayfinding proves relevant across fields.

6. Lessons for Modern Wayfinding Practice

From Stars to Satellites

The art of Polynesian wayfinding may have been honed in the context of oceanic exploration, but its principles are not confined to the sea. The same skills that guided a double-hulled canoe to a pinpoint of land over the horizon can guide modern teams, technologies, and societies through uncertainty today.

Sources: Traditional navigators never relied on a single source of information.

Knowledge System: A star path is more than one star; a voyage is more than one route. Wayfinders always had alternatives in mind, whether for shifting winds or unexpected storms.

Trust: GPS can fail. The brain, properly trained, is remarkably resilient. Navigators cultivated mental charts that could be updated instantly without a device.

Learn by doing: No apprentice became a navigator from chants alone. The ocean was the classroom; feedback was immediate and often unforgiving.

Values: Polynesian wayfinding was never value-neutral. Voyages served community needs, honored ancestors, and respected the environment.

| Wayfinding Principle | Traditional Application | Modern Application |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-source observation | Combining stars, swells, birds, clouds | Integrating diverse datasets for decision-making |

| Redundant routes | Star paths, seasonal routes, alternate islands | Contingency planning in projects and logistics |

| Mental mapping | Dynamic, relational charts without coordinates | Adaptive strategy models for shifting conditions |

| Experiential mastery | Progressive training voyages | Simulation and applied learning in professional fields |

| Value-based navigation | Serving community, honoring environment | Aligning goals with ethics and sustainability |

Conclusion — The Horizon Within Reach

From the ancient Lapita mariners who first crossed the vast Pacific, to Tupaia translating an ocean’s memory onto paper, to modern crews guiding Hōkūleʻa across the world’s seas, Polynesian wayfinding has been an unbroken conversation between people and their environment.

It is at once science and art, discipline and intuition, history and living practice.

The wayfinders’ genius lies not only in their ability to find land without instruments, but in their deeper understanding: the ocean is not empty. It is filled with patterns, signals, and relationships waiting to be read. In their hands — and in their minds — navigation became a way of seeing, one that honors connection, adaptability, and the quiet authority of nature.

In our own age of satellites and screens, this knowledge offers both a challenge and an invitation. The challenge: to resist surrendering all navigation — literal or metaphorical — to machines. The invitation: to train our senses, trust our minds, and align our journeys with values that endure beyond the latest technology.

Like young Kainoa in our opening story, we are all apprentices at the bow, eyes fixed on a horizon we cannot yet see. The swells may rise, the winds may shift, but the signs are there for those who have learned to read them. And when we do, we discover that the compass we seek has been with us all along — carried not in our hands, but in our minds, our cultures, and our shared human capacity to find our way.

Frequently asked questions (FAQ)

-

Did Polynesian navigators really sail thousands of kilometers without instruments?

Yes. Using stars, ocean swells, winds, clouds, and wildlife patterns, they completed intentional voyages across distances of over 4,000 km — centuries before European oceanic exploration.

-

How accurate were their navigation methods?

Remarkably accurate. Experimental voyages like Hōkūleʻa’s 1976 trip to Tahiti demonstrated landfall within a few kilometers of the target after weeks at sea, all without GPS or compasses.

-

Can these skills be applied today?

Absolutely. While most travel now uses modern tools, the observational and decision-making principles of wayfinding — redundancy, environmental awareness, and adaptive thinking — are valuable in leadership, science, and sustainability work.

Useful links for reading and notemaking

Polynesian Voyaging Society – Hōkūleʻa

https://www.hokulea.com

Official site of the Polynesian Voyaging Society, with voyage logs, educational resources, and updates on modern navigation training.Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand — Polynesian Navigation

https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/6t2/tupaia

Feature article exploring the revival of wayfinding and the cultural movement behind it.Tupaia’s Map — Journal of Pacific History

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00223344.2018.1512369

Academic paper analyzing the cartographic logic and cultural translation in Tupaia’s 1769 map for Captain Cook.David Lewis — We, the Navigators (Wiki)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/We,_the_Navigators

Seminal study of Pacific navigation techniques based on fieldwork with master navigators.